Overview

The Blue Ridge Parkway’s involvement with the Pinnacles of Dan was a long, convoluted partnership between different local and federal agencies that ultimately ended in failure. Despite the Parkway’s ultimate decision to not develop the Pinnacles of Dan as a scenic site on the Parkway, the National Park Service’s long, four year partnership with the City of Danville and the Public Works Administration (PWA) during the construction of the Danville hydro-electric dam revealed many of the tensions as well as successes surrounding the issue of land use during the New Deal.

While the National Park Service (NPS), the PWA, and the City of Danville all had differing attitudes as to what constituted conservation, all agreed that the Pinnacles of Dan site should be conserved despite the construction of the dam and that successful conservation would lead to further Blue Ridge Parkway (BRP) development of the site. Despite worries over budget, miscommunications, mistakes during construction, and interpersonal conflicts between the men involved, the building of the dam represented a remarkable achievement of government partnership and cooperation.

The Pinnacles area is still a popular recreational spot today despite the lack of the Parkway. In addition, the Parkway’s involvement on the Pinnacles of Dan hydro-electric project offers interesting lessons into the history of environmental conservation and reflects debates that are still on-going about whether wilderness and civilization can exist side by side.

The Beginning

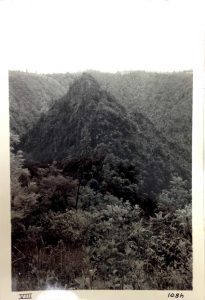

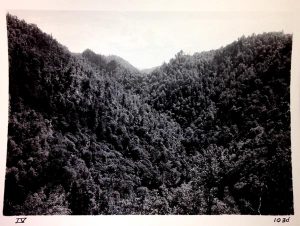

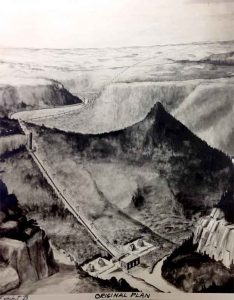

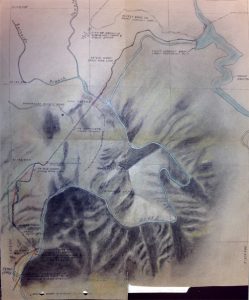

After scouting out suitable sites, resident landscape architect of the BRP, Stanley W. Abbott, and fellow landscape architect Edward H. Abbuehl, drafted a preliminary Blue Ridge Parkway Master plan [link to Blue Ridge Parkway Master plan] in December of 1934. As part of the proposed plan, the Pinnacles of Dan were to be one of the four lynchpin sites that would make up the skeleton of the Blue Ridge Parkway, along with an additional nine sites that would connect these key areas.[1] The Pinnacles of Dan feature two mountain peaks that jut out from the Dan River Gorge and are connected by a valley known as the ‘bowl’ area.

The pinnacles are described as “…a “miniature grand canyon” with a “startling degree” of “remoteness, wildness and ruggedness,” and that their unique and vivid naturalness were what made the site worthy of inclusion.[2] According to those who wished to see the site’s inclusion, there was nothing like the Pinnacles of Dan anywhere else in that area. However, despite these ardent wishes, it was clear that contention between the NPS, PWA, and City of Danville would be a significant obstacle for the inclusion of the Pinnacles on the Parkway.

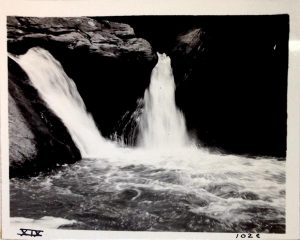

While the BRP leadership had their sights set on including the Pinnacles of Dan area, the City of Danville had plans in motion to use the area for their hydroelectric facility. In 1933, the city had applied for and received approval for a loan totaling $3, 000, 000 from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation that would be used in building and developing a hydroelectric facility that would provide municipal power for the City of Danville. The city ended up withdrawing their application at that time but in January of 1935, they formally requested a re-allocation of the federal loan from the PWA. [3] Concurrently, NPS Associate Director A.E. Demaray also filed an objection stating that the hydroelectric development would mar the scenic beauty of the area. The city was ultimately granted $1, 237, 909 with the additional money to be raised in bonds but it was clear that no resolution had been made as to which group would have authority over the site.[4]

The City of Danville was quite adamant that the only feasible site for their hydroelectric facility was to at Dan River Gorge. They disregarded the fact that army engineers had already surveyed another location, Smith Mountain Gap, and determined that it was well suited for this type of facility, if not better than the Dan River Gorge site. The city was worried that they would lose autonomy to the federal government at the Smith Mountain Gap location and thus chose to pursue only the Dan River Gorge site, even though it is located 85 miles away from Danville. Danville was certain that they could have their hydroelectric facility and the BRP, even declaring that the facility would be hidden by the rugged terrain and would add recreational value to the area that would attract more tourists since the dam would create a lake that could be used for fishing and other aquatic sports. They also claimed they would make every effort to conserve and keep damage to a minimum.[5]

Issue of Conservation

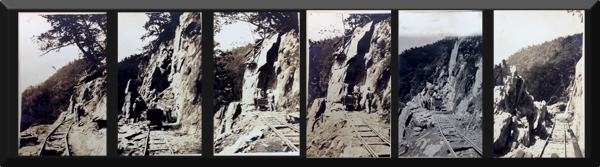

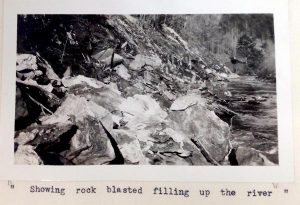

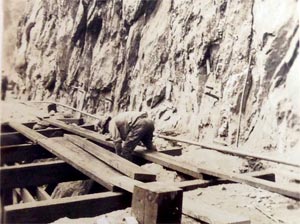

When it was certain that the facility was to be built, Demaray requested that Abbott continue on the project in an advisory capacity. [6] Abbott was tasked with advising on preventing damage to the wilderness and promoting conservation, even though that advice was often overlooked. Abbott tried to be removed from the project, as he could not see any viable way to have the hydroelectric facility and maintain the natural beauty and scenic value of the unique Pinnacles of Dan area. Abbott had originally thought it possible to retain the site but he assumed that precaution would be taken during construction and that damage would be minimal. This was proven untrue as construction progressed and Abbott was particularly concerned with the ruthless way service roads were being constructed and took issue with the uncontrolled level of blasts that were being used to clear the rock from the area. [7] The NPS rebuffed the Abbott’s appeals and requested that Abbott continue working on the project with the City of Danville and the PWA and that he make routine inspections and further suggestions.[8]

C.W. Short [link to C.W. Short Conservation Report] was also tasked in the conservation effort as a PWA architect engineer and produced a report in August 1936 that outlined the Pinnacles of Dan area and specified key landscape features that had been damaged or might be damaged in future construction. [9] Shortly after this, the PWA hired Ralph D. Patterson as the resident landscape architect for the project and he was supposed to act as a liaison between the PWA and NPS on the issue of conservation. This started a long and tense relationship, as Patterson would often go over J.R.A. Hobson Jr.’s head, his superior and PWA project engineer for the Pinnacles development, to confer with Abbott about conservation issues. Hobson did not appreciate the lack of chain of command and this eventually led to Patterson’s dismissal in June of 1937. Part of what led to Patterson’s dismissal was his involvement of the placement of Kibler Road through the bowl area. [10] The NPS considered the bowl area to be one of the prime scenic attractions and originally believed that Kibler Road would not go into the bowl area. Patterson did not inform his superior Hobson or his agency about meeting with Abbott and addressed his concerns directly to Abbott. Hobson took issue with this as he felt Patterson presented the Kibler Road project to be much more damaging to the area than it truthfully was and that it left Abbott with the impression that conservation was not being done.

In November 1936, the City of Danville requested a grant totaling $92,045 with the intended purpose of covering the cost of landscaping and conservation efforts of the Pinnacles project, particularly for creating a tunnel for one of the pipelines, planting, screening and restoration of the area around the power plant. [11] The city was to provide an additional $112, 500 to match the NPS service grant and in January of 1937, the grant request was approved. However, the City of Danville did not meet the expectations of the NPS and PWA on what was to be conserved and there was a recommendation that a total of $7,000 be withheld until such conservation could be completed.[12] The city saw this withholding as “unnecessary and unwarrantable” since they felt they had in fact used the money for the conservation of the recreational area as it was intended.[13] The NPS thought otherwise and Demaray was concerned with the scarring he still saw in the bowl area and surrounding features. Later in August, there was an additional allotment of $200,000 that was to be used for the Big Bend Reservoir, with the intention that part of it was to be used for the conservation effort and effort towards replanting and correcting the spoil from the blasting sites.[14] It was suggested that $30,000 be withheld as collateral to ensure that the conservation did in fact occur. However, the NPS was unable to withhold the money, as it was determined that the entire grant would be needed to complete the hydroelectric facility.

Conclusion

In March of 1938, the contractors and CCC labor finished the last of the conservation planting for the tank and bowl area. Then on June 7th, 1938, there was a dedication ceremony for the completion of the Pinnacles Hydro-electric Plant. A month later Abbott re-evaluated the site and determined that the original reasons for including the site were no longer reasonable as the dam construction had vastly changed the wilderness. [15] It would also be too difficult to try and acquire the lands at this point as the main tracts of land were under private ownership including the “Lipscomb Tract” owned by the local lumber company, Rosslyn Lumber Company. Later in 1941, Harry F. Byrd offered to buy the “Lipscomb Tract”, which seemed to smooth the way for inclusion of the Pinnacles of Dan on the Blue Ridge Parkway but Demaray rejected the offer, blatantly showing that the NPS had lost interest in including this site by this time. [16]

[1]Firth, Ian. “Blue Ridge Parkway Virginia and North Carolina: Historic Resource Study.” working paper., University of Georgia , 2005.

[2] Avery, M. H. Letter to Associate Director NPS A.E. Demaray. 1935, March 20. RG 79, National Park Service, Central Classified Files, 1933-1949 (Entry #7B), National Parkways, Blue Ridge, Box 2735. National Archives II, College Park, MD.

[3] Jenkins, R.L. Letter to Right-of-way Engineer Branch of Plans & Design National Park Service C.K. Simmers. February 9,1935. RG 79, National Park Service, Central Classified Files, 1933-1949 (Entry #7B), National Parkways, Blue Ridge, Box 2735. National Archives II, College Park, MD.

[4] Docket No. 1151 R — Danville, VA. 1936. RG 79, National Park Service, Central Classified Files, 1933-1949 (Entry #7B), National Parkways, Blue Ridge, Box 2735.

[5] Aiken, A. M. Letter to Deputy Administrator of the Federal Emergency Administration of Public Works Major Philip B. Flemming. 1935, February 27. RG 79, National Park Service, Central Classified Files, 1933-1949 (Entry #7B), National Parkways, Blue Ridge, Box 2735. National Archives II, College Park, MD.

[6] Demaray, A.E.. Memorandum to Stanley Abbott. April 30, 1936. Blue Ridge Parkway Archives, Record Group 6, Old Land Acquisition Files, Series 29, Pinnacles of Dan Correspondence Files 1934-1937, Box 13 BLRI-7986.

[7] Abbott, Stanley W. Memorandum to Mr. Vint. July 7, 1936. Blue Ridge Parkway Archives, Record Group 6, Old Land Acquisition Files, Series 29, Pinnacles of Dan Correspondence Files 1934-1937, Box 13 BLRI-7986.

[8] Demaray, A.E.. Memorandum to Stanley Abbott. July 31, 1936. Blue Ridge Parkway Archives, Record Group 6, Old Land Acquisition Files, Series 29, Pinnacles of Dan Correspondence Files 1934-1937, Box 13 BLRI-7986.

[9] Short, C.W.. Report to the Director, Engineering Division on visit to the Pinnacles of Dan. August 17-22, 1936. Blue Ridge Parkway Archives, Record Group 6, Old Land Acquisition Files, Series 29, Pinnacles of Dan Correspondence Files 1934-1937 Box 13 BLRI-7986.

[10] Patterson, Ralph D.. A Report in Words and Pictures of the Construction of the Kibler Road.” 1937. Blue Ridge Parkway Archives, Record Group 6, Series 31, Box 15 BLRI-7896.

[11] Demaray, A.E.. Memorandum to Secretary. November 6, 1936. Blue Ridge Parkway Archives, Record Group 6, Old Land Acquisition Files, Series 29, Pinnacles of Dan Correspondence Files 1934-1937, Box 13 BLRI-7986.

[12] Hobson, J.R.A. Jr. Memorandum to E.C. Brantly. July 13, 1937. Blue Ridge Parkway Archives, Record Group 6, Old Land Acquisition Files, Series 29, Pinnacles of Dan Correspondence Files 1934-1937 Box 14 BLRI-7986.

[13] Gorman, Sheridan P. Memorandum to Dr. Clark Foreman. July 20, 1937. Blue Ridge Parkway Archives, Record Group 6, Old Land Acquisition Files, Series 29, Pinnacles of Dan Correspondence Files 1934-1937 Box 14 BLRI-7986.

[14] Gorman, Sheridan P.. Memo to E.C. Brantley. August 23, 1937. Blue Ridge Parkway Archives, Record Group 6, Old Land Acquisition Files, Series 29, Pinnacles of Dan Correspondence Files 1934-1937 Box 14 BLRI-7986.

[15] Abbott, Stanley W. Report to the Director of the National Park Service. August 12, 1938. Blue Ridge Parkway Archives, Record Group 6, Old Land Acquisition Files, Series 29, Pinnacles of Dan Correspondence Files 1934-1937 Box 14 BLRI-7986.

[16] Demaray, A.E.. Letter to Harry F. Byrd. August 2, 1941. Blue Ridge Parkway Archives, Record Group 6, Old Land Acquisition Files, Series 29, Pinnacles of Dan Correspondence Files 1934-1937 Box 14 BLRI-7986